Farming in mid-nineteenth century Barwick

from The Barwicker No.7

September 1987

Back to the Main Historical Society page

Back to the Barwicker Contents page

History can be compiled from the most unlikely sources. The 1861 Rating Assessment Book for the Barwick township, recently deposited in the Leeds District Archives at Sheepscar, seems more likely to induce hostility than historical curiosity. Yet it contains such detailed and comprehensive information about the land and its uses that much of the economic life of the township in the mid-nineteenth century can be reconstructed.

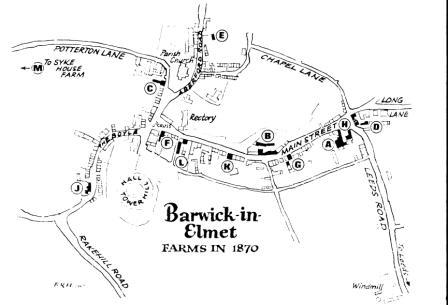

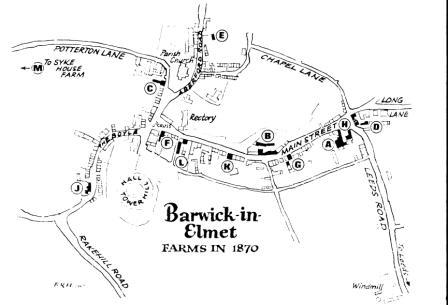

The book records the division of the land into plots, 1300 or more in the township as a whole and about 400 in and around Barwick village. Each plot is numbered and can be located on a map drawn in 1870 and kept at Sheepscar.

The owner of each plot is named. There were three big landowners in the township; the Rector of Barwick (the Rev. Charles Augustus Hope), the Lord of the Manor (Frederick Gascoigne Esq.) and Bathurst Edward Wilkinson Esq., who owned Potterton and Kiddal. Barwick township owned about 70 acres, the rents from which were used for the relief of the poor. There were only two other substantial landowners in and around Barwick village; Benjamin Crosland, with about 50 acres, and Henry Scholfield, with about 170 acres. Other holdings were small, but numerous; in all, 57 individuals or institutions owned land i vi property in and around Barwick village.

The names are also given of the occupiers of each plot, that is those who lived there or who worked the land. Dwellings on each plot are described; houses, cottages, farmhouses, etc., as are farm buildings; barns, cowsheds, stables, sheds, etc. Other business premises are included; inns, beerhouses, blacksmiths, butchers, slaughterhouses, mills, lime-kilns and quarries. Public buildings include churches and schools.

The area of each plot is given, together with its rateable value and its gross estimated rental, which in 1861 was 120% of the rateable value. Plots without buildings are listed by use; jrass, arable and woodland, of which there was little in Barwick. Grassland made up about one third of the toal agricultural land, much of it in the immediate surroundings of the village. The low-lying land on the banks of Rakehill Beck, Long Lane Beck and Cock Beck was also given over to grass.

The field names given in the book appear for the most part to be of no great age and were probably just devices to enable the rates assessor to distinguish between the fields in a farmer's holding. Some are named after the pre-enclosure open fields and commons: Richmond Field, High Field, Low Field, Little Field, Whinmoor. Others refer to the surnames of some present or past occupier: Robshaw's Close, Low Clemmishaw. Some indicate some aspect of their history: Far Intake, Encroachment. Some are descriptive: Thistly Shaw, Shoulder of Mutton (from its shape). What are the origins, one wonders, of Frying Pan Start, which dates from pre-enclosure times, or of Polly Garth?

The book shows that there were 12 farms in the Barwick area, ail in the village except Syke House Farm. Rakehill Farm and Verity's Farm, Richmondfield Lane, had not then been built. All the farmers were essentially tenants, some having a single landlord and others several. Only three owned their own farmhouses. Only a few farms had their fields united in a compact block, most had them scattered around the area surrounding the village. This appeared to be the rule whether the farm was owned by one landlord or several. It probably arose from the necessity for each farm to have a share of the pasture and meadow available.

The farms and farmers are listed below. No farm names are given in the book, so the modern names are given. Where a farmhouse no longer exists, the approximate present address of its site is given.

Drawing by Bart Hammond

The working lives of these farmers and their labourers are not easy to reconstruct. Little was written about them at the time and not much of this has survived. It is the legal, administrative and financial documents of the time that remain and sometimes they give us a clue to farming practices. We are fortunate that many of the business documents of the rectors of Barwick still survive. They were the owners of land worked by tenant farmers and some of the agreements for the lease of this land are still preserved at Sheepscar.

Two of these are of particular interest. The first, dated 1826, is between Rector Bathurst and Richard Perkin and it concerns 90 acres of what is now Lime Tree Farm. The second, dated 1853, involves Rector Hope and Matthew Wilkinson and is the lease of the Rectory Farm, which then comprised 140 acres. The main themes of the agreements are self-sufficiency and conservation, especially the maintenance of the fertility of the land. They indicate little change in farming methods during the quarter of a century between the dates.

The annual rents of the farms were £120 and £147 respectively, the tenant paying the rates and taxes. The tenants agreed to maintain in good order the dwellinghouse, outbuildings, hedges, drains, ditches, gates, stile-posts, rails and fences. The art of hedging is well described in the 1826 lease. "And once at the leaf in every year (the tenant shall) weed and dress all the quick set fences and supply fresh quick sets when necessary and keep the young fences well and effectively protected from cattle and when and so soon as the same shall arrive at a sufficient growth to make a good fence, they shall be laid and at all time during the said term kept dressed and preserved...".

These were mixed farms, like all those in Barwick village in the mid-nineteenth century. One third of the total acreage was grassland - meadow, which was cut for hay, and pasture for grazing animals. This proportion was not accidental; it was stipulated in the lease. This amount of land supported enough livestock to produce sufficient manure to maintain the fertility of all the land on the farm. The agreements ensured that all the manure produced was used on the farm. The meadows had to be manured every two years. No grassland was to be ploughed up without leave under penalty of £20 an acre as extra rent. The animals would include horses for ploughing, drawing wagons and riding. Cattle have been previously mentioned and all the farms had cow-shedsĄ Whether or not sheep were kept is not stated.

The sequence of crops grown on the arable land was also regulated by the leases. The early agreement specifies " a due and regular course of good husbandry according to the most approved mode of management pursued in the country". This was a four year cycle, including a fallow year. The purpose of the fallow was to break up and clean the soil, removing weeds before the advent of chemical sprays.

Three types of fallow are mentioned. In a summer fallow, no crop was grown but the land was worked to control the weeds. In a turnip fallow, the land was sown late with turnips after some work to control the weeds. William Cobbett in his "Rural Rides" describes the method he saw in one of his rare visits to Yorkshire in the second decade of the century. The turnips were grown on ridges with sufficient space between to allow horse or hand hoeing. The turnips were dug up and used as winter feed for cattle, rather than grazed by sheep, the method he saw in the South of England. All the turnips had to be consumed on the farm. A potato fallow was similar, with the crop grown in flat rows, not ridges as today.

After the fallow, the land was ploughed in the late winter or early spring, using, at that time, a single-blade plough drawn by two horses. Corn, usually barley, was then sown by hand. Winter barley had not then been developed. The barley was probably harvested by scythe or some other hand implement. Horse-drawn reaping machines had been developed at the time but they were crude instruments and didn't come into general use until they were improved later in the century. The reaper-and-binder wasn't introduced until the 1890's.

It is likely that the barley was threshed by hand using a flail. Threshing machines had been developed, driven first by horses and then in the 1840's by steam, but they didn't come into general use until the 1860's. All the straw produced had to be used on the farm.

The lease stipulated that, if there was insufficient permanent pasture or meadow, some of the barley at the two leaf stage should be sown down with grass or clover, so that at all times one acre in three was grassland. After the barley was harvested, the grass or clover would grow away and establish itself before winter. It would then be used in the following year for grazing or hay.

For the year following the barley, the lease of 1853 required "a green crop of clover, beans, peas or tares". These are legumes, which fix atmospheric nitrogen by forming bacteria-filled root nodules. These increase the fertility of the soil by releasing nutrients as they break down. All the produce of this green crop had to be consumed on the farm, presumably for fodder or compost. Other fertilisers mentioned are rape dust, left after the extraction of oil, and guano. A crop of spring-sown wheat completed the four-year rotation. It would then be threshed by hand and ground into flour at the windmill in Leeds Road.

The Gascoigne estates books are kept in the Leeds Archives and they include details of the crops grown in individual fields during the 1860's and 1870's. The Barwick farms are not included but those of Lotherton are typical of the district. For a farm with only a small proportion of grassland the usual cropping pattern was:

For farms with more grassland, beans, peas and rape replaced seeds in Year 3. In very few years were there any fields without crops. No attempt was made to change arable to pasture or vice versa.

The leases stated that the tenant must not sow flax, teazles or woad without leave in writing. These were crops used by the clothing industry and were often grown as two-year crops. This would make it difficult to keep the fields weed free and they would use up a lot of the soil nutrients. The tenant was also prohibited from growing mustard or rape for seed. These would leave the land very dirty as much seed would be lost at harvest-time and might remain viable in the soil for years.

The leases also laid down conditions for changes in tenancy. These usually occurred on May-day, so "waygoing crops" had to be sown ready for the next tenant and all the agreed fallows had to be made for land cleaning. All the timber and minerals belonged to the landlord, as did the hunting and shooting rights. The tenant was also required to supply the landlord with wheat straw and to lead coal for him.

The working lives of the farmers and their labourers in the mid-nineteenth century must have been hard. Most tasks were carried out by hand, using simple implements. Apart from horses, no power was available.

The agricultural workers of the time were nothing if not versatile. Tasks on the Barwick farms would include hedging, ditching, ploughing, leading, sowing, weeding, harvesting, haymaking, threshing, milking, care of animals and perhaps shearing. Much of the produce would be surplus to the requirements of the farm and the village and would be sold to feed the increasing population of Leeds - flour, barley, milk and beef.

The author wishes to thank Mr.D.Hardy of Leeds University Farm for expert assistance in the writing of this article.

Back to the Main Historical Society page

Back to the Barwicker Contents page

Back to the Barwicker Contents page

History can be compiled from the most unlikely sources. The 1861 Rating Assessment Book for the Barwick township, recently deposited in the Leeds District Archives at Sheepscar, seems more likely to induce hostility than historical curiosity. Yet it contains such detailed and comprehensive information about the land and its uses that much of the economic life of the township in the mid-nineteenth century can be reconstructed.

The book records the division of the land into plots, 1300 or more in the township as a whole and about 400 in and around Barwick village. Each plot is numbered and can be located on a map drawn in 1870 and kept at Sheepscar.

The owner of each plot is named. There were three big landowners in the township; the Rector of Barwick (the Rev. Charles Augustus Hope), the Lord of the Manor (Frederick Gascoigne Esq.) and Bathurst Edward Wilkinson Esq., who owned Potterton and Kiddal. Barwick township owned about 70 acres, the rents from which were used for the relief of the poor. There were only two other substantial landowners in and around Barwick village; Benjamin Crosland, with about 50 acres, and Henry Scholfield, with about 170 acres. Other holdings were small, but numerous; in all, 57 individuals or institutions owned land i vi property in and around Barwick village.

The names are also given of the occupiers of each plot, that is those who lived there or who worked the land. Dwellings on each plot are described; houses, cottages, farmhouses, etc., as are farm buildings; barns, cowsheds, stables, sheds, etc. Other business premises are included; inns, beerhouses, blacksmiths, butchers, slaughterhouses, mills, lime-kilns and quarries. Public buildings include churches and schools.

The area of each plot is given, together with its rateable value and its gross estimated rental, which in 1861 was 120% of the rateable value. Plots without buildings are listed by use; jrass, arable and woodland, of which there was little in Barwick. Grassland made up about one third of the toal agricultural land, much of it in the immediate surroundings of the village. The low-lying land on the banks of Rakehill Beck, Long Lane Beck and Cock Beck was also given over to grass.

The field names given in the book appear for the most part to be of no great age and were probably just devices to enable the rates assessor to distinguish between the fields in a farmer's holding. Some are named after the pre-enclosure open fields and commons: Richmond Field, High Field, Low Field, Little Field, Whinmoor. Others refer to the surnames of some present or past occupier: Robshaw's Close, Low Clemmishaw. Some indicate some aspect of their history: Far Intake, Encroachment. Some are descriptive: Thistly Shaw, Shoulder of Mutton (from its shape). What are the origins, one wonders, of Frying Pan Start, which dates from pre-enclosure times, or of Polly Garth?

The book shows that there were 12 farms in the Barwick area, ail in the village except Syke House Farm. Rakehill Farm and Verity's Farm, Richmondfield Lane, had not then been built. All the farmers were essentially tenants, some having a single landlord and others several. Only three owned their own farmhouses. Only a few farms had their fields united in a compact block, most had them scattered around the area surrounding the village. This appeared to be the rule whether the farm was owned by one landlord or several. It probably arose from the necessity for each farm to have a share of the pasture and meadow available.

The farms and farmers are listed below. No farm names are given in the book, so the modern names are given. Where a farmhouse no longer exists, the approximate present address of its site is given.

| Farm | Tenant | Acres | |

| A | Lime Tree Farm | Margaret Perkin | 102 |

| B | Rectory Farm | Matthew Wilkinson | 179 |

| C | Church Farm | Thomas Robshaw | 88 |

| D | Glebe Farm | George Robinson | 67 |

| E | Low Farm | John Hemsworth | 34 |

| F | Gascoigne Farm | William Knapton | 53 |

| G | 58/60 Main St. | William Thompson | 91 |

| H | 74 Main St. | Thomas Barton | 137 |

| J | 56/58 The Boyle | William Varley | 49 |

| K | 30-36 Main St. | William Connell | 110 |

| L | 16 Main St. | Richard Newby | 30 |

| M | Syke House Farm | Zechariah Appleyard | 109 |

Drawing by Bart Hammond

The working lives of these farmers and their labourers are not easy to reconstruct. Little was written about them at the time and not much of this has survived. It is the legal, administrative and financial documents of the time that remain and sometimes they give us a clue to farming practices. We are fortunate that many of the business documents of the rectors of Barwick still survive. They were the owners of land worked by tenant farmers and some of the agreements for the lease of this land are still preserved at Sheepscar.

Two of these are of particular interest. The first, dated 1826, is between Rector Bathurst and Richard Perkin and it concerns 90 acres of what is now Lime Tree Farm. The second, dated 1853, involves Rector Hope and Matthew Wilkinson and is the lease of the Rectory Farm, which then comprised 140 acres. The main themes of the agreements are self-sufficiency and conservation, especially the maintenance of the fertility of the land. They indicate little change in farming methods during the quarter of a century between the dates.

The annual rents of the farms were £120 and £147 respectively, the tenant paying the rates and taxes. The tenants agreed to maintain in good order the dwellinghouse, outbuildings, hedges, drains, ditches, gates, stile-posts, rails and fences. The art of hedging is well described in the 1826 lease. "And once at the leaf in every year (the tenant shall) weed and dress all the quick set fences and supply fresh quick sets when necessary and keep the young fences well and effectively protected from cattle and when and so soon as the same shall arrive at a sufficient growth to make a good fence, they shall be laid and at all time during the said term kept dressed and preserved...".

These were mixed farms, like all those in Barwick village in the mid-nineteenth century. One third of the total acreage was grassland - meadow, which was cut for hay, and pasture for grazing animals. This proportion was not accidental; it was stipulated in the lease. This amount of land supported enough livestock to produce sufficient manure to maintain the fertility of all the land on the farm. The agreements ensured that all the manure produced was used on the farm. The meadows had to be manured every two years. No grassland was to be ploughed up without leave under penalty of £20 an acre as extra rent. The animals would include horses for ploughing, drawing wagons and riding. Cattle have been previously mentioned and all the farms had cow-shedsĄ Whether or not sheep were kept is not stated.

The sequence of crops grown on the arable land was also regulated by the leases. The early agreement specifies " a due and regular course of good husbandry according to the most approved mode of management pursued in the country". This was a four year cycle, including a fallow year. The purpose of the fallow was to break up and clean the soil, removing weeds before the advent of chemical sprays.

Three types of fallow are mentioned. In a summer fallow, no crop was grown but the land was worked to control the weeds. In a turnip fallow, the land was sown late with turnips after some work to control the weeds. William Cobbett in his "Rural Rides" describes the method he saw in one of his rare visits to Yorkshire in the second decade of the century. The turnips were grown on ridges with sufficient space between to allow horse or hand hoeing. The turnips were dug up and used as winter feed for cattle, rather than grazed by sheep, the method he saw in the South of England. All the turnips had to be consumed on the farm. A potato fallow was similar, with the crop grown in flat rows, not ridges as today.

After the fallow, the land was ploughed in the late winter or early spring, using, at that time, a single-blade plough drawn by two horses. Corn, usually barley, was then sown by hand. Winter barley had not then been developed. The barley was probably harvested by scythe or some other hand implement. Horse-drawn reaping machines had been developed at the time but they were crude instruments and didn't come into general use until they were improved later in the century. The reaper-and-binder wasn't introduced until the 1890's.

It is likely that the barley was threshed by hand using a flail. Threshing machines had been developed, driven first by horses and then in the 1840's by steam, but they didn't come into general use until the 1860's. All the straw produced had to be used on the farm.

The lease stipulated that, if there was insufficient permanent pasture or meadow, some of the barley at the two leaf stage should be sown down with grass or clover, so that at all times one acre in three was grassland. After the barley was harvested, the grass or clover would grow away and establish itself before winter. It would then be used in the following year for grazing or hay.

For the year following the barley, the lease of 1853 required "a green crop of clover, beans, peas or tares". These are legumes, which fix atmospheric nitrogen by forming bacteria-filled root nodules. These increase the fertility of the soil by releasing nutrients as they break down. All the produce of this green crop had to be consumed on the farm, presumably for fodder or compost. Other fertilisers mentioned are rape dust, left after the extraction of oil, and guano. A crop of spring-sown wheat completed the four-year rotation. It would then be threshed by hand and ground into flour at the windmill in Leeds Road.

The Gascoigne estates books are kept in the Leeds Archives and they include details of the crops grown in individual fields during the 1860's and 1870's. The Barwick farms are not included but those of Lotherton are typical of the district. For a farm with only a small proportion of grassland the usual cropping pattern was:

For farms with more grassland, beans, peas and rape replaced seeds in Year 3. In very few years were there any fields without crops. No attempt was made to change arable to pasture or vice versa.

The leases stated that the tenant must not sow flax, teazles or woad without leave in writing. These were crops used by the clothing industry and were often grown as two-year crops. This would make it difficult to keep the fields weed free and they would use up a lot of the soil nutrients. The tenant was also prohibited from growing mustard or rape for seed. These would leave the land very dirty as much seed would be lost at harvest-time and might remain viable in the soil for years.

The leases also laid down conditions for changes in tenancy. These usually occurred on May-day, so "waygoing crops" had to be sown ready for the next tenant and all the agreed fallows had to be made for land cleaning. All the timber and minerals belonged to the landlord, as did the hunting and shooting rights. The tenant was also required to supply the landlord with wheat straw and to lead coal for him.

The working lives of the farmers and their labourers in the mid-nineteenth century must have been hard. Most tasks were carried out by hand, using simple implements. Apart from horses, no power was available.

The agricultural workers of the time were nothing if not versatile. Tasks on the Barwick farms would include hedging, ditching, ploughing, leading, sowing, weeding, harvesting, haymaking, threshing, milking, care of animals and perhaps shearing. Much of the produce would be surplus to the requirements of the farm and the village and would be sold to feed the increasing population of Leeds - flour, barley, milk and beef.

The author wishes to thank Mr.D.Hardy of Leeds University Farm for expert assistance in the writing of this article.

| Arthur Bantoft |

Back to the Main Historical Society page

Back to the Barwicker Contents page