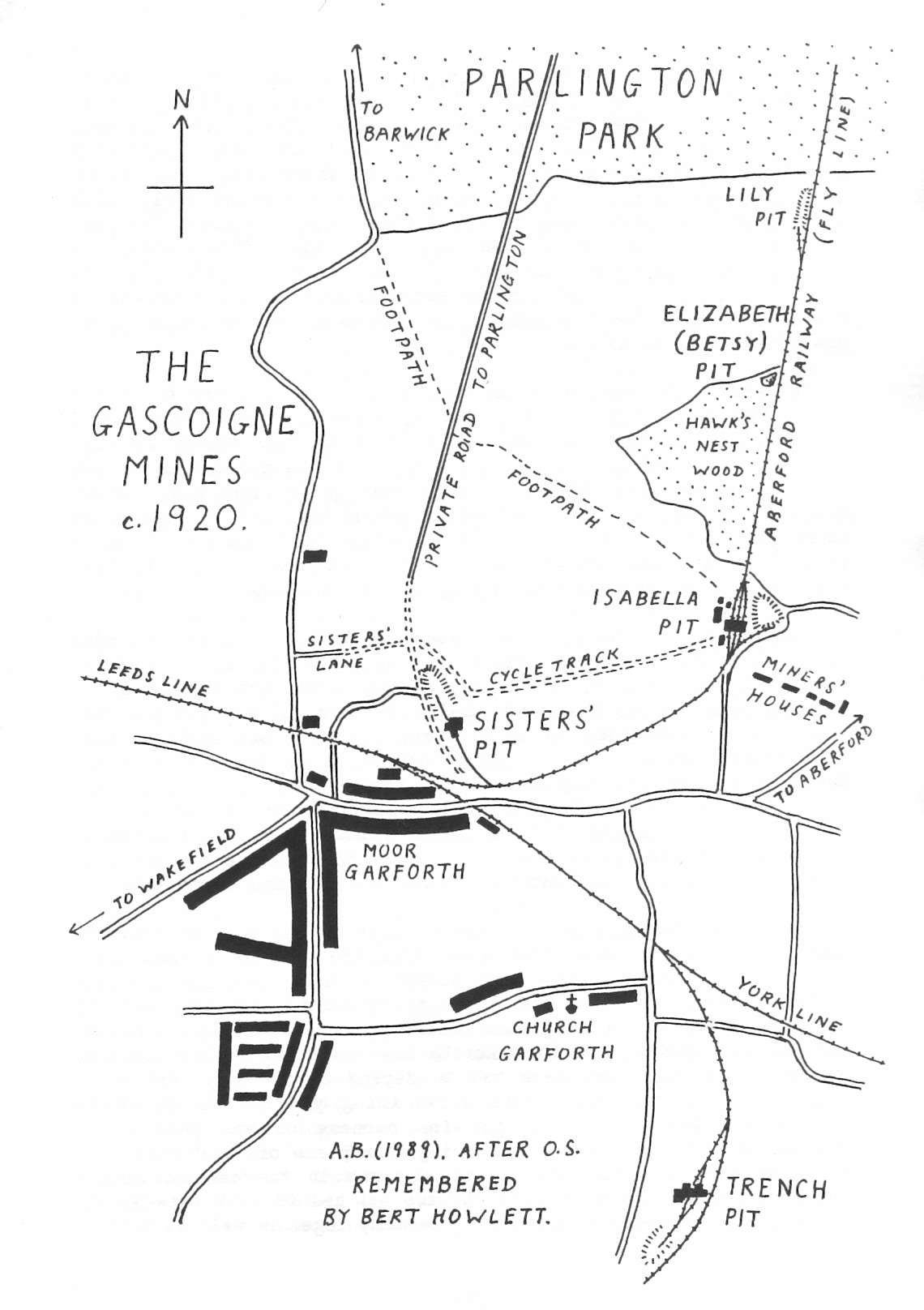

A Barwick Miner Remembers

from The Barwicker No.14

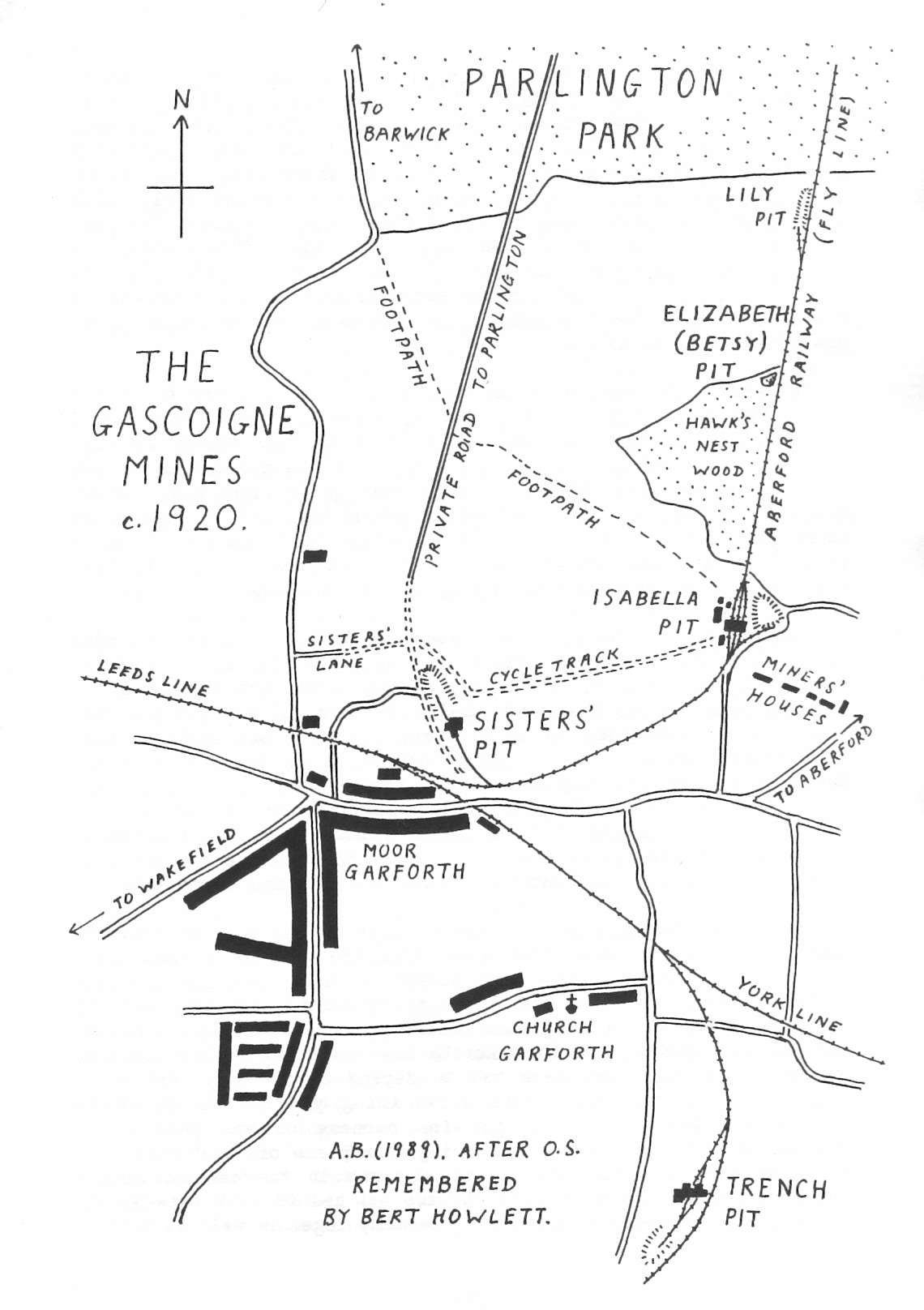

June 1989 | The drawing of Isabella Mine is taken, with permission, from

"The Aberford Fly Line History Trail" by Graham Hudson. |

| The drawing of Isabella Mine is taken, with permission, from

"The Aberford Fly Line History Trail" by Graham Hudson. |